First published February 1, 2018

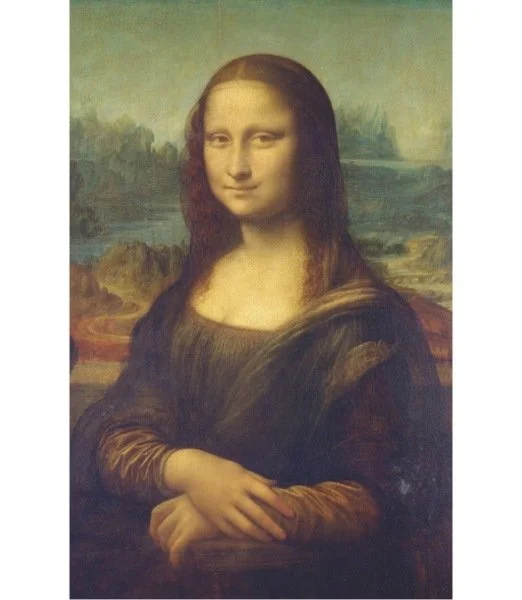

Having written a little about Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, it’s time to turn the spotlight on another work by the Renaissance genius.

This is the cartoon of The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John The Baptist, formerly known as The Burlington House Cartoon. It hangs in the National Gallery in London. A cartoon is the preparatory sketch for a painting. The finished cartoon was mounted on a board and holes were pricked around the outline and key features. Chalk was then pounced through the holes to make an outline to guide the painter. This particular cartoon was never pierced and thus we know that the intended painting was never done.

It is a very unusual pose. Mary is sitting on the lap of St Anne, her mother. She holds her son, Jesus, who is blessing the baby St John.

I assume Leonardo chose this pose as a means of representing both women in a very intimate space. I don’t think it an altogether satisfactory pose and it is telling that is was not adopted by other artists who were otherwise influenced by Leonardo.

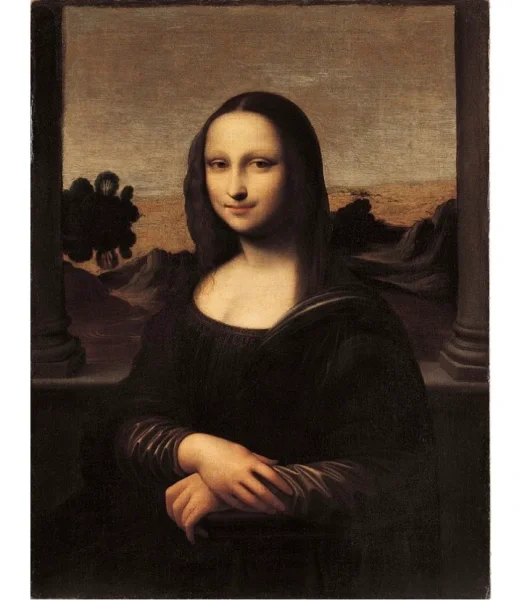

This next Leonardo image is in the Louvre and is titled The Virgin and Child with St Anne.

Something caused Leonardo to alter his design.

According to Wikipedia, ‘This subtle yet perceptible distortion in size was utilised by Leonardo to emphasise the mother daughter relationship between the two women despite the apparent lack of visual cues to the greater age of St Anne that would otherwise identify her as the mother.’

Tortured, or what?

Meanwhile, the Economist notes, ‘A monumental Anne sits with her adult daughter perched on her lap. Mary reaches out trying to keep a grip on Jesus who is half-straddling a lamb.’ (Leonardo da Vinci’s “St Anne” 29 April 2012).

Why would Jesus be half-straddling a lamb?

St Anne does not appear in the Bible. She is mentioned in the apocryphal Gospel of James. Let’s say that she is eighteen years older than Mary. Which of the two women portrayed looks older? The foreground figure surely? And remember, this is Leonardo da Vinci, a man obsessed with drawing faces, and unbelievably proficient at doing so. If he had wanted to draw a young woman he would have. He did, lots of times.

Traditionally, Mary was young when she gave birth to Jesus, again let’s imagine seventeen or eighteen. Is there another candidate for the foreground figure? What about Elizabeth, mother of John the Baptist who was thought to be beyond childbearing age when she became pregnant as a result of a miracle? Could she be the forty-something year old woman on Mary’s lap?

If she is, we can make sense of the other change, the appearance of the lamb. If the foreground woman is Elizabeth, the child could be John, who later in life would utter the words, “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” [John 1:29] At the time of the scene portrayed, Jesus is yet unborn and so is represented by the lamb.